So, which is more important?

HAVING SOMETHING TO SAY

Or

HOW YOU SAY IT?

Obviously, both are terribly important. If you have the most influential, consequential message in the world, but mumble it and use words that mean nothing to your audience, no one will get the message. And so, thinking about words and logic and order and speaking style are critical and necessary, and HOMILETICS (the study of preaching) certainly has a lot to say about HOW you say it.

But I’m going to vote for HAVING SOMETHING TO SAY as being the most important. Jesus is the greatest Teacher this world has ever seen—because He had something to say. He spoke the Truth. He spoke the Words of the Father. He said His Words were life, if they were eaten people would never be hungry again. People were amazed, they walked for miles into the desert to hear Him. They sat without eating for hours to listen to Him. His Words have lasted for 2,000 years. Everywhere His Words are read and followed people are changed, societies reformed, and the world in that area gets better. Isaiah 55:10-12 says His Words have power to create what they say.

People don’t want to just listen to good-looking people who speak in perfect sentences but who say nothing. They want wisdom. They want big ideas. They want something that penetrates to the core of things, that moves the needle, that makes a difference in their lives.

People scan through articles, magazines, newspapers, scanning for things that jump out at them. They listen to sermons, with the gates of their minds 9/10 closed, waiting, wading through the cliches and banter and small talk, waiting for something that will be unique, fresh, hammered out on the anvil of life, experience, and deep thought and reflection. Then the gates open, and they receive it and ponder it and take it into their lives. If they wanted little ideas they can get that at the beauty parlor or barber shop.

But too much of the time the gates stay closed, the eyes glaze over, the mind begins to think of lunch and Saturday night, and the Sabbath afternoon nap has already begun. People stand up for the closing song, disappointed again, glad to see their friends, glad to check off going to church, but the longing for something to really bless them, feed them, move them, is unsatisfied again.

So—start with this—HAVE SOMETHING TO SAY!

So—HOW?

THEN go to work on HOW TO SAY IT!

It’s Monday morning, and you have to preach Sabbath. Or Wed. night, or give a worship at the school, or for the youth meeting Friday night. The need for sermon ideas is constant and endless! If you move from one place to the other and can dip into your “file,” not great, but OK. But most of the time, you’re hoping for inspiration to hit in the form of an idea—clever, fresh, inspiring, to you and to them.That will lead to a sermon that people will be talking about for weeks to come, and be remembered right up there with I Have a Dream, It’s Friday, But Sunday’s Comin’, or Sinners In the Hands of a Mighty God.

TRIANGLE:To make things as simple as possible, I think of it as a Triangle. At the top I would put #1, the BIBLE. We are people of the Word. A lot of the words came straight from Jesus. The Word is inspired, after all. We’re told to “Preach the Word”. People will grow from hearing the Word. They are hungry to hear a Word from God Himself. It’s promised that His Word “will not return to Me void”. So, why not start with the Bible?

Obviously, it’s easiest if you are working through a portion of the Bible, like a Gospel or the Psalms or 1 John, in your sermonic year, so you know you’re looking in the next chapter of the book for your sermonic idea. You’ve narrowed your search from over 1,000 pages down to 1! Or you might work with a lectionary, which assigns certain OT and NT texts for that week. But those are not the only places to get an idea. It might come from your daily devotional. It might come from a sermon you heard, from a Tim Keller podcast or streaming Randy Roberts. It might come from a Philip Yancey or Max Lucado or Morris Venden book you’ve been reading. Either way, the idea comes from the Bible, you already have a text, and you can start with a Bible open to that page and a blank pad and you’re halfway there.

#2, YOU.But many times, the idea doesn’t come first from the Bible, it starts with you. Your soul. Your questions. Your spiritual journey. And, to the degree that you are an Everyman or Everywoman, and your experience parallels that of many of your listeners, it’s a safe bet that digging into and answering your own issues and questions and needs will help a lot of your people.

Obviously, starting with “you” will help with preaching with authenticity, honesty, and freshness, because you are speaking out of your own passions. If you find an answer to your question during the week, you will preach with a mind and heart on fire because God gave you something that week that spoke to you, ministered to you, blessed you, and that will always add a spark and sparkle to your message.

One important distinction might help right here, the difference between inductiveand deductive preaching. Deductive preaching starts with a thesis or premise, and then backs it up and applies it through the rest of the sermon. People know where you’re headed from almost the beginning of the message. The disciples said, “Teach us to pray.” Thesis: Prayer is something you can learn. OK. Everybody relaxes. They’ve got it. Now you back it up what Jesus taught, what you have learned yourself, and coaching your people how they should pray. But people knew pretty quickly the Big Idea.

Inductive preaching, on the other hand, starts with a question or an issue. Hopefully it’s an issue or question they have also, and they’re hooked. But you don’t answer it quite yet. You present possible answers, ideas you have had in the past, or what other people have thought. Then you go to the text, to see what answers it may have for them—and you hopefully have held their interest through the search, the mystery, and the detective work, trying to get to the bottom of this thing.

Sermons that start with You will probably fall more into the inductive style, but you can go deductive also. “Here’s what I have found”—and dive in. But you may enjoy keeping the tension for awhile, and draw them in by making them part of the team to dig out the answer to this universal question that you personally got stuck on this week!

#3, the CONGREGATION. The third corner of the Triangle is the Congregation. The sermonic idea may come up during your pastoral visitation. Or from a text or email. Or from the Pastor’s Class. Or from the potluck. Or from an elder who says, “People are wondering….” God, in Exodus 3, looked down at the world, saw His children struggling with slavery in Egypt, and said “I am coming down to do something about this.” The need rose out of the people’s experience. Nicodemus came slithering through the shadows of the night with a question to Jesus, and we got John 3 out of the deal. The disciples asked Jesus about the Last Days, and we got Matthew 24.

The blessing of getting the sermonic idea out of the congregation, is that you have a fighting chance to be more relevant than usual, because you know already that at least some have this very question. They give a slight nod, and they’re happy that their pastor or speaker has the good sense to know a good issue or question when they see it. They’re also happy because their pastor is in touch, aware, awake, and not just living in a monastery or ivory tower and coming down to earth for a couple hours a week with something from some big books in their library or from class notes from Seminary!

I had a retired pastor preach for me in one small church in Oregon, on homosexuality. I thought to myself, “Why did he do that? Had he heard we had that issue? Did he think that, out of all the things he could have preached on, that that was the most important?” I had a doctor give a health talk on asthma, 20 minutes on asthma. Had he heard that a lot of people there were dealing with that? Another lady doctor spoke on menopause. Why? Most of the audience did not identify with that subject! I invited my younger brother, still in college, to come be an intern for the summer, preaching in my other church every week. I asked him, “What are you going to preach about this week?” “Sin.” Why? What was it about our church that told him he needed to clarify things about sin? Well, it turned out it was because he had just taken a class on sin at La Sierra!

Some preachers put pictures of a few of their memories above their computer screen. But one way or the other, your people have to be a big part of this sermonic idea process. You’re visualizing them, praying about them, talking to them, listening for their concerns, writing down their questions, taking surveys, whatever you can do to draw them out. I had a sermon group for years, which, yes, helped wrestle with my ideas, but also brought many ideas from their own lives for me to preach about.

Now, to wrap this up: IT DOESN’T MATTER WHICH POINT OF THE TRIANGLE YOU COME INTO THE SERMON IDEA FROM—AS LONG AS YOU DO JUSTICE TO THE OTHER TWO CORNERS! If you start with the Congregation, you still have to make sure that you are excited about the search and answers, or the sermon will fall flat. You will still have to make sure that you don’t twist and distort the Bible passage in order to meet the unique and specific needs of your church that week.

I had a guest, from the Evangelism Department of the Conference, want to inspire the members to get out of their comfort zone and witness in our town. But he used the text about the eagle and the nest, and said that the eagle pushes its babies out of the nest, and we should get out of our nest. No, that is NOT what the text said! The babies fell out, and the mother eagle caught them on her wings and brought them back to the nest! The very opposite point he was trying to make. I’m sure it’s a good idea to get out and witness! But that was the wrong text for his agenda!

If you start with the Bible, you have to fight hard to make sure that you are relevant to the questions of and the world of your congregation. If you start with your own issues and questions and journey, you have to make sure that you are a good representative of the typical people in your congregation, and that you are honest with the text, not letting your powerful bias on this topic distort what you read out of the text. One of our favorite writers wrote, “We have much to learn and much to unlearn.” We may often have to let the text critique our ideas, and nudge us into new and scary territory, but with the assurance that God only leads us upward and closer to capital T Truth!

God bless you all!

That the Bible is the authoritative standard for faith and practice implies not only its truthfulness and trustworthiness but also that the Bible is sufficiently clear to be understood correctly. This conviction is repeatedly affirmed by the biblical writers and by Jesus Christ Himself. Questions such as “Have you not read?” (Matt. 12:3, 5; 19:4; 22:31; Mark 12:26) or references to “It is written” (Matt. 4:4, 7, 10) or such statements as “Whatever was written in former days was written for our instruction, that through endurance and through the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope” (Rom. 15:4, ESV) indicate that Jesus and the apostles expected people to be able to read and understand the meaning of Scripture accurately so that they could practice it faithfully.

Why Are Some Bible Passages Difficult to Understand?

In stark contrast to skeptics and critics of the Bible, the Bible writers affirm the truthfulness of Scripture and do not give any clear warrant for the belief in the existence or prevalence of errors that would question the Bible’s infallible authority and reliability. One reason that some perceive apparent mistakes in the Bible is that they rely on a poor translation that might convey a wrong or misleading meaning of the original words. To understand difficult statements in Scripture, it is best to have a thorough knowledge of the biblical languages and to study the Bible in Hebrew and Greek. Where this is not the case, one should at least compare several good Bible translations before drawing any conclusions.1 It is possible that some mistakes have occurred in the process of transmitting the Bible manuscripts.2 Yet those minor mistakes that have crept in through the subsequent process of copying and translating Bible manuscripts are so insignificant that not one honest soul need stumble over them.3

Yet the question remains: Why are some Bible passages difficult to understand? Even the apostle Peter knew about the challenge to understand some of Paul’s writings “in which are some things hard to understand, which untaught and unstable people twist to their own destruction, as they do also the rest of the Scriptures” (2 Peter 3:16). The challenges of such difficult passages in the Bible have been recognized by serious students throughout history, and we do well to remember that most likely we are not the first readers of Scripture to discover them. It is quite probable that other careful scholars of Scripture have noted the same difficulty long before us and most likely have come up with a solution. Just because I am not acquainted with a solution to a problem in Scripture does not mean that no solution exists.4

This brief article cannot deal with all aspects relating to the interpretation of the Bible,5 but here are some thoughts that can help relative to dealing with Bible difficulties.

Dealing With Difficulties in Scripture

Peter states that only “some things” are hard to understand with Paul. Not all things are difficult to understand! In fact, most things in Scripture are quite clear and can be understood very well. We should not let the few statements in the Bible that are more difficult darken the many passages that are clear. We must decide whether we want to build our faith on things that are uncertain and hard to understand or whether we want to build our faith on those things that are very clear. An important principle of biblical interpretation is that we should always move from the clear statements of Scripture to those that are less clear. We aim to shed light from the clear statements of the Bible on those passages that are more challenging. Never the other way around.

In dealing with biblical statements, we also need to remember that the Bible writers frequently used nontechnical, ordinary, everyday language to describe things. For example, they spoke of sunrise (Num. 2:3; Joshua 19:12) and sunset (Deut. 11:30; Dan. 6:14), i.e., they used the language of appearance rather than scientific language. One must not confuse a social convention with a scientific affirmation. The need for technical precision varies according to the situation in which a statement is made. Therefore, imprecision cannot be equated with untruthfulness. Furthermore, the biblical writers did not write in a technically perfect yet unknown heavenly Esperanto, but in ordinary everyday language. All human language is deficient in its ability to describe the totality of reality. Yet the language that is used by the biblical writers is not misleading in what it describes, but faithfully reflects what God wanted to communicate through it. Even fallible human beings are fully capable to communicate truthfully. Hence the repeated warning in Scripture not to change or add anything to the written Word (Deut. 4:2; 12:32; Rev. 22:18, 19).

In dealing with difficulties in Scripture, we must also remember that many so-called mistakes are not the result of God’s revelation, but are the result of the misinterpretation of humans. Ellen White has pointed out that “many contradictory opinions in regard to what the Bible teaches do not arise from any obscurity in the book itself, but from blindness and prejudice on the part of interpreters. Men ignore the plain statements of the Bible to follow their own perverted reason.”6 Thus, often the problem is not so much with the biblical text but rather with the interpreter. It has been said that for some people the most difficult Bible verses are not those passages that are difficult to understand, but rather those statements of Scripture that they can clearly understand but are not willing to obey.

This leads to another challenge in biblical interpretation that we often face when dealing with difficult passages. There is a negative effect of sin on our understanding of Scripture. Sin darkens our understanding of God’s Word and leads to pride, self-deception, doubt, and a distortion of meaning that ultimately ends in disobedience.7 Unwillingness to follow God’s revealed will negatively affects our ability to grow in our understanding of Scripture and to interpret it correctly. Disobedience and deliberate sin are effective barriers to knowing God’s truth (Ps. 66:18). A persistent opposition to God’s revealed truth leads to a point in which the disobedient person is unable to hear and understand God’s Word properly.

Approaching Scripture With the Right Spirit

So what does it take, then, to approach the study of God’s Word, including those difficult passages, with the right spirit?8

Maintain integrity: When we deal with a difficult passage in Scripture, we do well to approach it in perfect honesty. God is “pleased with integrity” (1 Chron. 29:17, NIV). This implies, first, that we acknowledge a difficulty and do not try to obscure or to evade it. An honest person has an open mind set that is receptive toward the message and subject matter of what is being studied. Furthermore, honesty includes the willingness not to twist the evidence or to come to premature conclusions because of a lack of evidence. In biblical and archaeological studies the absence of external evidence is no evidence for the absence of things that are affirmed by Scripture. Honesty also requires the use of proper methods of investigation. To explain and understand the Word of God correctly, we cannot use methods with naturalistic presuppositions that are based on atheistic premises that run counter to God’s Word.

Deal with difficulties prayerfully: Prayer is no substitute for hard work and thorough study. In prayer, however, we confess that we are dependent upon God to understand His Word. It is an expression of humility that acknowledges that God and His Word are greater than our human reason and even greater than our current understanding. On our knees we can ask for the leading of the Holy Spirit and gain a new perspective of the biblical text that we would not have had if we had placed ourselves above the Word of God.

Explain Scripture with Scripture: With God as the ultimate author of Scripture, we can assume a fundamental unity among its various parts. This means that to deal with challenging aspects of Scripture, we need to deal with all difficulties scripturally. The best solution to Bible difficulties is still found in the Bible itself. There is no better explanation than explaining Scripture with Scripture. This means that we must compare Scripture with Scripture, taking into consideration the biblical context in which a statement is found.

Be patient: While all the aspects mentioned above can help in dealing with any difficulty in Scripture with confidence, it will not always produce an easy or swift solution. We must be determined that no matter how much time and study and hard thinking it may require, we will patiently work on finding a solution. At the same time, as we wrestle with difficult Bible passages we should focus on the main points and not get overwhelmed by or get lost in some insignificant details. And if some problems persistently defy even our hardest efforts to solve them, we should not get discouraged. Perhaps God has allowed some difficult parts of Scripture to exist to demonstrate how determined we are to study its meaning and how important the Bible is to us. Part of our perseverance is to be able to live with open questions, yet to joyfully embrace and obey the many passages that are clear to us.

1 For a recent evaluation of the strength and weaknesses of various Bible translations from an Adventist perspective, see Clinton Wahlen, “Variants, Versions, and the Trustworthiness of Scripture,” in Frank M. Hasel, ed., Biblical Hermeneutics: An Adventist Approach (Silver Spring, Md.: Biblical Research Institute, 2020), pp. 63-103.

2 Ellen G. White, Selected Messages (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1958, 1980), book 1, p. 16; cf. Ellen G. White, The Great Controversy (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1911), p. 246.

3 E. G. White, Selected Messages, book 1, p. 17.

4 Some recent books that deal with difficult Bible passages are Gerhard Pfandl, Interpreting Scripture: Bible Questions and Answers (Silver Spring, Md.: Biblical Research Institute, 2017); Gleason L. Archer, Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1982), and Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., Peter H. Davids, F. F. Bruce, and Manfred T. Brauch, Hard Sayings of the Bible (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1996).

5 If you want to dig deeper and explore important aspects of biblical interpretation, see the discussion in Frank M. Hasel, ed., Biblical Hermeneutics: An Adventist Approach.

6 Ellen G. White, “Thoroughness in Christian Work,” Review and Herald, Jan. 27, 1885, par. 8.

7 See Frank M. Hasel, “Presuppositions in the Interpretation of Scripture,” in George W. Reid, ed., Understanding Scripture: An Adventist Approach (Silver Spring, Md.: Biblical Research Institute, 2005), pp. 30-32.

8 In the following I follow closely Frank M. Hasel, “Are There Mistakes in the Bible?” in Gerhard Pfandl, ed., Interpreting Scripture: Bible Questions and Answers (Silver Spring, Md.: Biblical Research Institute, 2017), pp. 38-40.

Is light a wave or particle? In some ways light behaves like a wave, and in other ways light behaves like a particle. How can both be true? Scientists still struggle to make sense of this.

Have you ever wondered how God could be one and three? If so, you have wondered how the Trinity doctrine makes sense. This article addresses this question and the even more important issue of why it matters—exploring how the Trinity is vitally important to our entire faith and practice.

The Basic Biblical Doctrine of the Trinity

In my last Discipleship of the Mind article we saw that Scripture teaches the basic Trinity doctrine: There is only one God, and God is three distinct fully divine persons.1

Laid out in three points:

1. There is only one God (e.g., Deut. 4:35, 39; 6:4; James 2:19; John 5:44).

2. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are each (fully) divine (e.g., Acts 5:3, 4; Heb. 9:14; 1 Cor. 2:10, 11; John 1:1-3; 8:58; 20:28; Col. 2:9; Heb. 1:2, 3, 8).

3. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct persons (e.g., Eph. 4:30; 1 Cor. 2:11; 12:11; John 14:26; 15:26; cf. Matt. 3:16, 17; 28:19).

These three points, repeatedly taught by Scripture, amount to the basic Trinity doctrine.

How Can God Be One and Three?

But does the teaching that God is one and God is three persons amount to a contradiction? No. This would be contradictory only if it claimed God is one and three in the same way.

Think of a three-leaf clover. It is only one clover, but has three leaves. A three-leaf clover, then, is one and three in different ways. This involves no contradiction. I do not mean to suggest that the Trinity is one and three in the same way as a three-leaf clover. All analogies for the Trinity are inadequate because God—as Creator—is incalculably greater than any creaturely reality. I mention a three-leaf clover only to show that something can be one and three in different ways without any contradiction. According to Scripture, God is one in the sense of being one God and three in the sense of being three persons. The three persons are united as one God.

But, you might ask, how are the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit united? The Bible does not directly tell us. God is far beyond our understanding. We know God only through what He has chosen to reveal (see Deut. 29:29). Given this, it is best not to speculate beyond what God has revealed.

The Bible does teach, however, that there is only one God and that God is three distinct fully divine persons. Precisely how is this so? I don’t claim to know. I also don’t know how God is eternal or how God is all-powerful. Do you? Of course not. But we do not need to know how God is eternal and all-powerful in order to believe and affirm that God is eternal and all-powerful. I believe these teachings because Scripture teaches that God is eternal (Ps. 90:2; 1 Tim. 1:17) and all-powerful (Jer. 32:17; Rev. 19:6). Even if these teachings are beyond our limited human understanding, believing and affirming these things does not involve any contradiction. There is mystery here, but no contradiction.

As noted earlier, even the brightest human thinkers still don’t understand how to make sense of the fact that light sometimes appears to behave like a wave and other times like a particle. We should not be surprised, then, that we do not fully understand God’s nature. As the Creator of all, God transcends all creaturely limitations (Ps. 145:3; Isa. 55:9) and is beyond all conceptions of being that are familiar to us.

One might be tempted to try to put God in a conceptual box—to limit what is true about God to what we currently understand. But that would be a huge mistake if we want to know the living God of the Bible. God is always greater than even our best understanding of Him. The things I believe about God, then, should be not be grounded in what I think I have grasped according to my puny human “wisdom,” but should be grounded in that which is far greater than myself or my understanding—what God has revealed in Scripture.

As John Wesley once put it: “I believe . . . that God is Three and One. But the manner how I do not comprehend.” Yet “would it not be absurd . . . to deny the fact because I do not understand the manner? That is, to reject what God has revealed, because I do not comprehend what he has not revealed?”2

Why Does the Trinity Doctrine Matter?

Yet why does this matter? What difference does it make for our faith and practice? I will list just seven ways the Trinity is essential to our faith and practice. The Trinity matters because:

1. Biblical truth matters, and whom we worship matters.

Only God is worthy of worship (e.g., Ex. 34:14; Matt. 4:10). If Christ is not God, it is blasphemy to worship Christ, and Christianity is utterly false. But Christ is God and the Father Himself commands creatures to worship Christ (Heb. 1:6).

2. Christ’s identity is essential to our faith and practice.

We cannot be Christians without following Christ. If we do not know the truth about Jesus’ divinity, we cannot answer for ourselves the all-important question Jesus asked: “Who do you say that I am?” (Matt. 16:15). It is no coincidence that the enemy attacks the Trinity doctrine and the divinity of Christ specifically. The question of who is worthy of worship is central to the great controversy.

3. The Holy Spirit’s identity is essential to our faith and practice.

The Holy Spirit’s identity is inseparable from the Spirit’s crucial role in the plan of salvation. Jesus promised that He and the Father would send the Holy Spirit as another “Helper” or advocate in Christ’s place (John 14:16, 17; 15:26). But the Holy Spirit could be another advocate like Christ only if He is also fully divine.

Further, we do not know how to pray as we ought, but the Holy Spirit “makes intercession for us with groanings which cannot be uttered” (Rom. 8:26). Only one who is God could intercede for us in this way. And the Holy Spirit inspired Scripture, without which we would know very little about God. But who could know the things of God except the Spirit of God (1 Cor. 2:11)? In these and many other ways the Holy Spirit’s identity is essential to our connection to God.3

4. The plan of salvation could not make sense apart from the Trinity.

Only One who is both God and human could reconcile God and humans. And if Christ is not God, the crucifixion was merely a human sacrifice—akin to pagan child sacrifice. Rather than providing the ultimate display of God’s love and justice (Rom. 3:25, 26; 5:8), the cross would display only the worst kind of injustice. But Christ is God, and thus God (in Christ) chose to give Himself for us (see John 10:18; Gal. 2:2). God “has not required human sacrifice; he has himself become the human sacrifice.”4In this and other ways the very the story of redemption—the way God saves us in the great controversy—makes sense only if God is Father, Son, and Spirit.

5. God is love.

“God demonstrates His own love toward us, in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Rom. 5:8). But Christ’s giving His life for us could provide the ultimate demonstration of God’s love only if Christ is God. And, Paul wrote, “the love of God has been poured out in our hearts by the Holy Spirit” (verse 5). But the Holy Spirit could pour God’s love into our hearts only if He is God. In this and other ways (see, e.g., John 10:18), love itself is grounded in the Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

6. The Trinity makes sense of how God could freely create the world.

The Trinity explains how God could be love prior to the creation of the world. Think about it. Before God created the world, there was nothing but God. How, then, could it be that God is love (1 John 4:8, 16)? Before the world was, who did God love? If there was no one or nothing to love, how could God be love?

If, on the other hand, God is more than one person, then God could enjoy love within the Trinity before there was any creation. Before the world was, the Father loved the Son and the Spirit, the Spirit loved the Son and the Father, and the Son loved the Spirit and the Father.

God did not need to create the world. God needs nothing (Acts 17:25). But God freely created the world as a manifestation of His love, despite knowing the cost to Himself. His creation of this world, despite the incalculable cost to Himself, was a free decision. God is thus “worthy . . . to receive glory and honor and power,” for God “created all things,” and by God’s “will they exist and were created” (Rev. 4:11).

7. God’s identity deeply affects our relationship with God.

Understanding God’s identity as Father, Son, and Spirit deeply affects our relationship with God. The kinds of relationships we have depend on the nature of those involved. I care for Brenda, Joel, Lucy, and Bo. I have a unique kind of love, however, for Brenda, who is my wife, another unique kind of love for Joel, my son, and a very different kind of affection for Lucy and Bo, our two cats.

Much more so, the nature of God dramatically impacts the way we can and should relate to God and everyone else. In this and other ways, the Trinity doctrine is not an extraneous theological puzzle, but is central to everything. God is love. And, amazingly, we are invited to enter into love relationship with the one true God who is love (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the Trinity of love), whose unfailing love endures forever.

Conclusion

There is so much more to say about the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. We’ve only begun to scratch the surface. Of the things Jesus did during His earthly ministry alone, John wrote, “If they were written one by one, I suppose that even the world itself could not contain the books that would be written” (John 21:25).

This should remind us how much more there is to know—more than we can imagine. Recognizing this should prompt us to be humble regarding our own “wisdom” and more committed to studying and clinging to what God has revealed about Himself in Scripture.

1 See John Peckham, “Is the Trinity Biblical? The Trinity Doctrine in Three Points,” Adventist Review, February 2024, pp. 56-59. See, further, John C. Peckham, God With Us: An Introduction to Adventist Theology(Berrien Springs, Mich.: Andrews University Press, 2023), chaps. 4-6.

2 John Wesley, “On the Trinity,” in The Works of John Wesley (Albany, Oreg.: Ages, 1997), pp. 220, 221.

3 For more on the Holy Spirit’s works, see Peckham, God With Us, chap. 5.

4 Fleming Rutledge, And God Spoke to Abraham: Preaching From the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2011), p. 302.

There is a wide range of literary styles employed by many different writers in the Bible. The biblical writers worked in many different centuries without collaboration with each other, yet their writings amazingly cohere. The writers use numerous literary conventions because no single literary form would be adequate to provide comprehensive expression of divine glory. The biblical canon is greater than the sum of its many parts.1 Some today treat biblical narratives as merely stories for children that can be left behind as one grows more intellectually sophisticated. But this results in a shallow consideration of narrative texts.

Biblical narratives have their own integrity and authenticity and deserve careful attention to their unique expression. Instead of being nice stories for children and merely “secondary materials” for mature readers, biblical narratives call for alert and informed readers. Though having a simple surface texture, they are very sophisticated writing—valuable for their historicity and brilliant theological expression. This shouldn’t be surprising, as the Author is divine and abounds in skill and grace! Thankfully biblical narratives are more and more appreciated for being well written and historically accurate.

Unparalleled in Ancient Times

Regarding their historical value, temporal scope, and persuasive strategy, biblical narratives have no parallel in ancient times. Alone among ancient texts, they present a people who kept their historical memory alive—recognizing that the past affected the present and determined the future.

Biblical writers used unique rules of discourse, often anchoring facts in aesthetic frameworks. It is this record that caused one distinguished historian to declare the Bible as “the greatest surprise in the whole story” of history writing. There emerged a people “possibly more obsessed with history than any other nation that has ever existed. . . . It was this historical memory which made Israel a people.”2 The people of Israel “stand alone amongst the people of the ancient world in having the story of their beginnings and their primitive state as clear as this in their folk-memory,” in creating the history of a nation and even of humanity itself.3In short, “ancient Israel provides, therefore, a pocket-size example of the very rise of historiography.”4

The biblical canon, with it unprecedented scope, is now recognized as an important landmark in the development of history writing, including:

■ clarified customs.

■ ancient names and current sayings traced back to their origins.

■ monuments and decrees assigned concrete reasons and a slot in history.

■ persons, places, and pedigrees specified as if inviting the reader to check it out.

Scripture refers to other written records, such as the Book of Yashar or royal annals, because historicity matters. Writers anchored narratives in public and accessible traces of reality to undergird their veracity.

Unfolding Theology in Action

Narrative history thereby unfolds a theology in action—distinctly grounded in God’s providence and control, enjoining a remembrance of His wonders from Creation onward, including the Exodus from Egypt (an Old Testament focal point)—uniquely explaining the passing of time in reference to God’s covenantal relationship with His people. Hebrew writers wrote about real history. To the narrator, history is an affair between heaven and earth. God wants His creatures to know Him—biblical writers providing a long sequence of divinely inspired and historically valid narratives recording this. God is the author, the source and norm of truth who inspired the human writers. If we lose sight of this, we misunderstand the nature of biblical narratives, which provide inspired descriptions of what really happened.

Biblical narratives can be underread and overread, but should never be counter-read. The narrator always tells the truth and is straightforwardly reliable. Critics have tried to quarrel with the facts, with some calling the narratives fiction. But taken at face value, the narratives are accounts of truth communicated and recorded with highest authority. In terms of the internal established premises—and these alone must determine interpretation—readers cannot go far wrong if they do little more than follow the statements made and the incidents presented. Statements can be expressed in a cryptic manner, though, so it is important to be sensitive to possible implications.

Scripture’s narratives cover many issues, including how God deals with everyone, within the covenant line and outside of it, with the same standard of justice. This is seen through the repetition of key words and phrases, subtle comparisons, and even irony in the divine actions with different people and nations. The Bible’s verbal artistry, without precedent in ancient history and unrivaled since, operates with its own art and sequential linkages. We cannot separate the literary aspects from theology any more than we can separate word from thought. Every narrative breathes out a deliberate theological vision of reality. At its heart the Christian gospel itself is not an abstract system but a living story, which the divine Author often proclaims through narrative writing.

Paying Attention to Important Details

The nature of the parts, the vocabulary, and units are carefully governed by the whole biblical canon. Seemingly incidental details need to be noted with shrewd observation. Details apparently unnecessary earlier will become clear later. For example, the mention of Absalom cutting and weighing his hair seems extraneous—this detail regarding hair isn’t noted of David’s other sons. But later the significance of the detail becomes clear when Absalom’s hair gets caught in a tree—the lead-in to his death (2 Sam. 14:26; 18:8-14).

Such literary conventions as chiastic and panel structures highlight vital issues in the narrative as well. Careful study of biblical narratives is more than just an aesthetic study of craftsmanship, but not less than that. Of primary concern is to understand the truth of the text at a deeper level. Narrative texts do not come right out and announce their themes—hiding theology in plain sight.

Narrative sequences likewise aid interpretation. For example, Genesis covers approximately 2,500 years in 50 chapters—with the first two of those 50 chapters pausing over only seven days—an example of narrative time “slowing down”—indicating the importance of the Creator’s acts. Chapter 3 narrates the fall of Adam and Eve. The reader is not told how long they lived in Eden before they sinned. Instead, chapters 1 and 2 describe the “very good” world God created and chapter 3 suddenly presents the dreadful, all-encompassing, results of the Fall. This striking contrast reveals the deadly nature of sin.

Stories That Prepare Hearts and Minds

God, the Creator and Master Artist, chose to reveal Himself through a sacred story that resembles more the imaginative works of epic poets and tragedians than the rational abstract materials of philosophers and theologians. The gospel story spreads its light both forward and backward to connect and inform all biblical narratives, speaking of messianic promise and eschatological hope, of redemption and reconciliation. Through psalms and prophets, as well as the “epic” tales of the Old Testament—Abraham’s long circuitous journey, Joseph and his brothers, the Passover and Exodus—the divine Author, using poets, storytellers, and prophets, sought to instruct and prepare hearts and minds of people for salvation in Christ.5

The extraordinary technical inventiveness of the ancient Hebrew writers is increasingly acknowledged and extolled—including how biblical texts refer to other biblical texts. The way Hebrew writers allude to other biblical verses connects the texts together with an amazing, overarching unity.

Narrative writers often describe rather than state truths. For example, instead of providing abstract propositions about virtue or vice, narratives depict people in action. The commandment “You shall not murder” is propositional and direct. Far earlier, the narrative of Cain and Abel embodies the same truth without even using the word “murder.”

The extraordinary technical inventiveness of the ancient Hebrew writers include repetition (a major tool for underscoring a vital issue) and dialogue. Narrative dialogues are a vital key for understanding biblical narratives. Rarely involving more than two persons, the recorded dialogues often furnish a major insight into what the narrative is about. For example, the first chapter of the book of Job is a dialogue between God and Satan providing background to what happens to Job, and why. In Genesis 3 the dialogues of the Creator with Adam and Eve after their sin indicate the deadly nature of sin. In Genesis 4 God’s dialogues with Cain right after Cain murders his brother—assuring that God seeks to save the lost! Intriguing also is Abraham’s dialogue with God over the fate of the wicked cities of Sodom and Gomorrah (Gen. 18:20-23), as well as Moses’ numerous dialogues with God.

The Story of Jonah

In the book of Jonah the reader doesn’t discover the real reason Jonah refused to go to Nineveh at first until the last chapter through the dialogue of Jonah and God. There Jonah finally admits that he knew God would be merciful with Israel’s archenemy. In the concluding verses of the book, Jonah is reminded by God that His compassion and mercy are not divine flaws—and even extend to animals (Jonah 4:11)!

The narrator pays much more attention to the problematic character of Jonah than the violent practices of Nineveh—recording more of Jonah’s rebellion than Nineveh’s wickedness. The four chapters of the book thus highlight God’s boundless mercy to pagan sailors, violent Ninevites, and even to the petulant prophet himself in spite of his callous disobedience. Moreover, Jonah tries to hide from God’s presence (just as Adam, Eve, and Cain had earlier)—recalling sin’s appalling nature (Gen. 2:8; 4:9-16; Jonah 1:2, 10).

There are no textual indicators that the book of Jonah is a parable or anything but a true historical record. However, because of the obedient fish, worm, and wind, critics of Jonah’s book do not accept it as true history.6 Yet the opening words—“And it came to pass”—are used in many biblical narratives that are not questioned regarding their historicity.

More Than a Book

The God of heaven has authored a book! But truly it is more than a book. The biblical canon is not some disjointed collection of miscellaneous documents. Through its many writers and narratives we are confronted with an omnipotent God who is in earnest to communicate His ways and love to human beings, whom He loves more than His own life. The biblical canon has a power all its own. God awaits us in His text—the narratives being a major aspect of this holy historical record.

1 There are letters (Jer. 29); royal edicts (Ezra 1); songs (Isa. 5); sermons (Deut.), court records (2 Sam. 20:23-26), liturgical rubrics (Lev. 6), parables (2 Sam. 12), allusions to ancient Near Eastern myths (Isa. 51:9), genealogies (1 Chron. 1-9), codes of moral teaching (Ex. 20), accounts of battles (2 Kings 23), love songs (S. of Sol.), historical data (2 Kings 14:26-28), and especially numerous narratives.

2 Herbert Butterfield, The Origins of History (New York: Basic Books, 1981), pp. 80-82.

3 Ibid., p. 94.

4 Ibid., p. 95.

5 Ellen White eloquently addresses this issue: “The study of the Bible demands our most diligent effort and persevering thought. As the miner digs for the golden treasure in the earth, so earnestly, persistently, must we seek for the treasure of God’s Word” (Education [Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1903], p. 189).

6 For a fuller consideration of the Jonah narrative, see Jo Ann Davidson, Jonah, the Inside Story (Hagerstown, Md.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 2003).

In a world where diverse faith traditions coexist, the importance of constructive interactions with believers of other faiths cannot be overstated. The Bible records remarkable stories of interactions between the children of Israel and adherents of other faiths, offering insights for effective interfaith communication. Here are some examples: Abraham and Melchizedek (Gen. 14:18-20), Abraham and Abimelech (Gen. 20:1-17), Elijah and the widow of Zarephath (1 Kings 17:8-24), Elisha and Naaman (2 Kings 5), Jesus and the woman at Jacob’s well (John 4:1-42), and Peter and Cornelius (Acts 10). Below are 10 tips for fruitful interfaith interactions drawn from these passages.

1. Pray for Understanding and Guidance: Start by praying for God to remove any stereotypes and prejudices you might have toward people from other faiths. Seek God’s wisdom and align with His mission.

2. Educate Yourself: Take the initiative to learn about the basic tenets and practices of other faiths. This will reduce your ignorance and foster cross-cultural understanding and communication skills in personal interactions and professional settings.

3. Avoid Assumptions: Do not assume that followers of other faiths have no knowledge of the true God. Abraham made this mistake in his encounter with Abimelech by assuming that the fear of God was absent from Abimelech and his people (Gen. 20:11). God’s witnesses can be found in unlikely places on earth. This is highlighted in Jesus’ commendation of the Roman centurion’s faith: “Assuredly, I say to you, I have not found such great faith, not even in Israel!” (Matt. 8:10). In your interactions with people of other faiths, prayerfully ask the Holy Spirit to reveal to you where and how He is already at work in their lives and ask Him for the courage, wisdom, and humility to join Him on His terms. Such an approach recognizes that the power of Christian witness emanates only from the enabling power of the Holy Spirit. It took Peter courage, wisdom, and humility to confess before Cornelius’ household that “in truth I perceive that God shows no partiality. But in every nation whoever fears Him and works righteousness is accepted by Him” (Acts 10:34, 35). It also took humility to acknowledge that the Holy Spirit that descended on him and other disciples at Pentecost was the same Holy Spirit that descended on Cornelius and his household, although they were not yet baptized (verses 44-48). We need to recognize and accept the fact that our conventional approaches may not align with God’s missionary ways and also that “we know only a portion of the truth, and what we say about God is always incomplete” (1 Cor. 13:9, Message).1

4. Show Respect: Approach people of different faiths with respect, love, and a positive attitude, recognizing their worth as individuals created in the image of God, cherished by Him, and endowed with a certain understanding of who God is. Attentively listen to them, thoughtfully consider their viewpoints, and acknowledge any genuine insights they offer. Active listening involves suspending judgment and preconceived opinions so that one can really hear another’s perspective. Although deep theological differences between faiths can make dialogue challenging, particularly on topics where beliefs strongly diverge, remain calm and respectful even if the conversation becomes challenging or emotionally charged. Avoid responding defensively or confrontationally. Winning an argument should not come at the cost of losing the heart of the person you are conversing with. The overall goal of a respectful, loving, and positive attitude toward those who have different beliefs is to eliminate prevalent misconceptions and establish bridges of mutual understanding. People’s appreciation for your scriptural knowledge will emerge only once they have a clear sense of your genuine care. Never forget that “the strongest argument in favor of the gospel is a loving and lovable Christian.”2

5. Acknowledge Shared Beliefs and Values: Finding common spiritual values and principles with someone from a different faith tradition can be a good foundation for fruitful dialogue. This can create a bridge of understanding and help dispel misconceptions and stereotypes.

6. Ask Engaging Questions: Encourage deeper conversation by asking questions that invite the person you are conversing with to share more about their beliefs and experiences. On one hand, asking engaging questions helps reveal the underlying assumptions of the person you are conversing with. It also relieves you from constantly being in a defensive position. For example, if a Muslim asks you, “Do you believe that Jesus is the Son of God?” avoid immediately answering “Yes.” Instead, simply ask him or her, “What do you mean by that?” In doing so, you will avoid confirming some misguided notions that person might have about Jesus. On the other hand, asking questions will also help you avoid making assumptions about what the other person believes or practices based on stereotypes or preconceived notions. Just as you appreciate others giving you an opportunity to define your own beliefs and practices, do the same for them (see Matt. 7:12). It is important that when asking engaging questions, you avoid turning the conversation into a debate or divisive argument.

7. Speak Truth With Love: Speak about your faith and its uniqueness without belittling the faith tradition of the person you are conversing with. Arrogance damages your role as a witness for Christ.

8. Acknowledge Enrichment: Recognize that God can plan your interactions with individuals from other faiths to contribute to your spiritual growth, as seen in Abraham’s interaction with Melchizedek (Gen. 14:18-20) and Peter’s encounter with Cornelius (Acts 10). The encounter between Abraham and Melchizedek benefited both of them spiritually and materially, and (very likely) deepened their understanding of God’s universal sovereignty. In his encounter with Cornelius, Peter’s preconceived beliefs about who could be part of the Christian community were challenged. As a result, Peter’s and other early Christians’ understanding of God’s inclusive redemptive plan was broadened. This encounter was also a foundational moment in the history of the early church relative to the inclusion of Gentiles in the Christian fellowship.

9. Consider Timing: Be mindful of when and where you share information. Choose the right moment for meaningful conversations. According to Ellen White: “Many efforts, though made at great expense, have been in a large measure unsuccessful because they did not meet the wants of the time or the place.”3 Therefore, she advises that “while the teacher of truth should be faithful in presenting the gospel, let him never pour out a mass of matter which the people cannot comprehend because it is new to them and hard to understand.”4

In John 16:12 Jesus Himself refrained from instructing His disciples beyond what they could bear at that time. If such was Jesus’ approach with those He was with day and night for three and a half years, it would be unwise for us to do otherwise with people we encounter in our Christian witness.

Another good example of considering good timing for what we say is the case of Naaman, the top military officer in Syria, who was afflicted with a severe case of leprosy. Heeding the counsel of a young Israelite servant girl, he embarked on a journey to Israel in search of a remedy. Following Elisha’s directive, he immersed himself seven times in the Jordan River and experienced a miraculous cure. Upon his recovery, Naaman confessed, “There is no God in all the earth, except in Israel” (2 Kings 5:15), and proclaimed his firm commitment to worship only Yahweh from then on (verse 17). He approached Elisha with an unusual request for special consideration, however. He wanted two muleloads of earth from Elisha’s property and pleaded for forgiveness when he was required to escort the king of Syria to the temple of Rimmon (verses 17, 18). Surprisingly, Elisha told him only, “Go in peace” (verse 19). Jon Paulien explains that “for the primal religions of Naaman’s day, all gods were associated with one land or another. That meant that Naaman could not worship Yahweh, the God of Israel, in Syria unless he brought with him Israelite dirt to spread in his garden. When he wanted to worship Yahweh, he would kneel on the Israelite soil. When he entered the temple of Rimmon with the king, he would bow his head but not his heart.”5

When Elisha sent Naaman off in peace, he was neither condoning nor encouraging his actions. As in John 16:12, Elisha might have felt that this was not the right moment to give counsel to Naaman on these matters. Instead, he chose just to acknowledge his faith and commit him to God’s care, trusting that in His providence God would continue to reveal Himself to him. Several centuries later Jesus commended Naaman’s faith in contrast to that of His contemporaries (Luke 4:27). Ellen White adds, “God passed over the many lepers in Israel because their unbelief closed the door of good to them. A heathen nobleman who had been true to his convictions of right, and who felt his need of help, was in the sight of God more worthy of His blessing than were the afflicted in Israel, who had slighted and despised their God-given privileges. God works for those who appreciate His favors and respond to the light given them from heaven.”6

10. Practice Hospitality: Offering, accepting, or asking for hospitality has the potential of counteracting negative stereotypes, breaking down barriers, building trust, and fostering relationships, as seen in the exchanges between Abraham and Melchizedek and between Jesus and the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well. The act of hospitality displayed by Melchizedek (offering his bread, wine, and blessing to Abraham) and Abraham’s humble response to it paved the way for meaningful conversations between them. In John 4:7 Jesus took the initiative to ask for hospitality from the woman at the well: “Give me a drink.” This simple request set the stage for a life-changing conversation and led to a remarkable turn of events. Jesus and His disciples were invited to stay in the Samaritan town for two days—a surprising and uncommon occurrence in their time. Many Samaritans came to confess their faith in Jesus as the Savior of the world (verse 42).

Conclusion

Fostering positive relationships with people of all nations, cultures, and beliefs is an integral part of the Great Commission. A rephrased version of Matthew 28:19, 20, could say, “As you go about your daily lives, be intentional about making disciples of the people you interact with.” Given that the gospel represents the most extraordinary news that we could ever have the opportunity to proclaim, Christ invites each of us to let our faith in Him influence all aspects of our lives—family, school, professional, and social interactions. If people reject the gospel, it should not be because we misrepresented its essence in our interactions with them.

1 Texts credited to Message are from The Message, copyright © 1993, 2002, 2018 by Eugene H. Peterson. Used by permission of NavPress, represented by Tyndale House Publishers, a division of Tyndale House Ministries. All rights reserved.

2 Ellen G. White, The Ministry of Healing (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1905), p. 470.

3 Ellen G. White, Gospel Workers (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1892), p. 297.

4 Ellen G. White, Evangelism (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1946), p. 202.

5 Jon Paulien, “The Unpredictable God: Creative Mission and the Biblical Testimony,” in A Man of Passionate Reflection, ed. Bruce L. Bauer (Berrien Springs, Mich.: Department of World Mission, Andrews University, 2011), pp. 87, 88.

6 Ellen G. White, Prophets and Kings (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1917), p. 253.

The word “exegesis” may seem to be fancy jargon used by professional biblical scholars, without much relevance to the average Bible student. The word “exegesis,” however, is a biblical term used concerning Jesus Himself! According to John 1:18, Jesus “exegeted” the Father! “God the only Son, who is in the arms of the Father, He has explained [exegeomai, “exegeted”] Him” (NASB). The Greek word exegeomai, from which we get our English word “exegesis,” simply means to “explain.” To “exegete” the Scriptures is to explain their meaning.

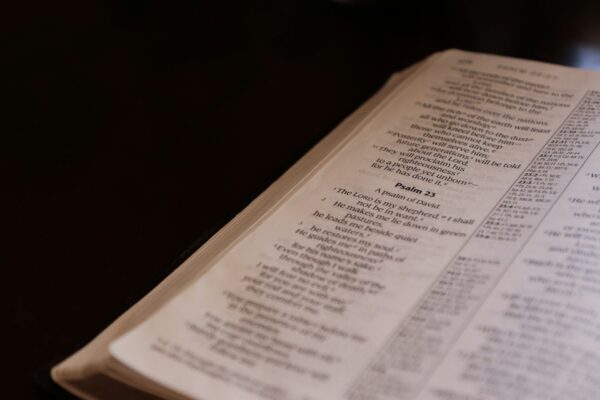

The process of biblical exegesis, as it emerges from Scripture’s own testimony, may be outlined in rough comparison with the Ten Commandments of Exodus 20. Just as the first table of four commandments deals with the divine-human (vertical) relationship, four general principles arise out of the divine-human nature of Scripture that form the foundational presuppositions of exegesis. Similarly, just as the second table of six commandments in the Decalogue deals with human (horizontal) relationships, the specific exegetical guidelines for the interpreter may be organized under six basic headings. Unlike the Decalogue of Exodus 20, this outline is not infallible! It represents one way of organizing the fundamental principles of exegesis. This article uses Psalm 23 as a case study illustrating how to apply these principles.1

The First Table of the Exegetical “Decalogue”: Foundational Presuppositions

I. The Bible and the Bible Only (Sola Scriptura)

The sola scriptura principle (Isa. 8:20) means that the Bible and the Bible alone is the rule of our faith and practice. Scripture alone is the final authority for truth, by which we judge all other authorities, such as tradition, philosophy, science, reason, and experience (Matt. 15:3, 6; 1 Tim. 6:20; Prov. 14:12). In Scripture we can breathe the “pure oxygen” of truth, and we use our reason, guided by the Spirit, not to critique, but to receive and understand Scripture (Isa. 66:2).

II. The Totality of Scripture (Tota Scriptura)

All Scripture is inspired by God and trustworthy (2 Tim. 3:16, 17; 2 Peter 3:14-16). Hence, we accept all of Scripture, not just the parts that fit our own predetermined worldview.

III. The Analogy (or Harmony) of Scripture (“Scripture Interprets Scripture”)

If all of Scripture is inspired by the same Spirit, then there is an underlying harmony among the various parts of the Word. The “analogy of Scripture” means that we allow Scripture to interpret Scripture (Luke 24:27; 1 Cor. 2:13). According to the biblical principle of the analogy of Scripture, we accept the consistency and clarity of Scripture (John 10:37; Deut. 30:11-14; Rom. 10:17).

IV. Spiritual Things Are Spiritually Discerned

“The things of the Spirit . . . are spiritually discerned” (1 Cor. 2:14). The Bible cannot be studied as any other book, coming merely “from below” with sharpened tools of exegesis. At every stage of the exegetical process, we need the Holy Spirit “from above,” to help us lay aside our own biased presuppositions, to see ever more the meaning of Scripture through His enlightenment, and to be spiritually transformed by that same Spirit (John 5:46, 47; 7:17; Ps. 119:33).

The Second Table of the Exegetical “Decalogue”: Specific Guidelines

The specific guidelines for exegesis of Scripture arise from and build upon the foundational presuppositions set forth in the “First Table.” This part sets forth practical steps in the exegetical process that emerge from the self-testimony of Scripture, applying them to Psalm 23.

V. Text and Translation

Since exegesis focuses on the written word of Scripture, it is vitally important that we have access to what are indeed the Holy Scriptures, not adding to or taking away from the inspired Word (Deut. 4:2; 12:32; Prov. 30:5; Rev. 22:18, 19), and faithfully translating the original languages into our modern languages (Neh. 8:8; Matt. 1:23). For those who cannot read biblical Hebrew or Greek, it is beneficial to read several (I suggest at least five!) translations of a biblical passage, to get an idea of the various possibilities of translating various words and phrases. For free online access to a variety of modern translations, see Bible Gateway (https://www.biblegateway.com). It is important to note that some modern versions provide a literal, word-for-word translation (e.g., NKJV, ESV, NASB), while others give a thought-for-thought translation (e.g., NIV, NLT) or a paraphrase (The Message). Each is good for its own purpose, but word-for-word translations are best for serious Bible study. To apply this guideline to Psalm 23, read this beautiful psalm over and over, in different versions!

VI. Historical Context

Scripture is largely a history book. In order to exegete the meaning of a passage of Scripture, we must first seek to grasp the historical context in which the Scripture was written. The superscription of Psalm 23 specifically indicates that it is “A Psalm of David” (Heb. mizmor le David). This phrase clearly indicates that David was the author of the psalm, written sometime during David’s life in the early tenth century B.C.2 In 1 Samuel 16 and Psalm 78:70 we find the background of David as a shepherd boy. We can examine the shepherd/sheep imagery of Psalm 23 elsewhere in the Scriptures (using a concordance or Bible with marginal references). We can view the psalm through the eyes of a shepherd to gain a knowledge of the behavior patterns of sheep.3

We can also learn about the geographical location of the areas where David probably led his sheep in the environs of Bethlehem. For example, Psalm 23:4 reads: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.” Archaeologists and biblical geographers have suggested that this phrase refers to a specific place in Palestine called “the Valley of Death.” It has been identified with the Wadi Qilt, which runs through the Wilderness of Judea from Jerusalem to Jericho. The wadi (a dry ravine except during rainy season) is some 15 miles long in total, and I have hiked (and camped) with my son through the entire gorge. The narrowest part passed through over five miles of cliffs reaching some 1,500 feet on each side, with space to walk at the bottom only 10-12 feet wide. There are numerous caves where wolves and other predators could hide in David’s time. At the end of the wadi, as it opens out, my son and I came upon a whole flock of sheep, lying in the pleasant grass shaded under the tall cliffs. The meaning of this verse came together in a powerful way!

VII. Literary Analysis

Scripture is also a literary work of art. Many verses, chapters, and even whole books of the Bible are structured in a special literary structure called a chiasm, in which the second half of the passage mirrors the first, and the central part often highlights the main point of the passage.

Psalm 23 has an intricate chiastic structure:

A. Presence: With God (verse 1)

B. Provisions: Needs Supplied (Food and Drink) (verses 2, 3a)

C. Paths: Righteousness (verse 3b)

C’. Paths: Shadow of Death (verse 4)

B’. Provisions: Needs Supplied (Food and Drink) (verse 5)

A’. Presence: With God (verse 6).4

We will return to the significance of this structure (and especially its apex) in the principle of theological analysis.

VIII. Verse-by-Verse Analysis (Word Studies, Grammar, Syntax)

The Bible comes alive as one looks at the rich meaning of various biblical words, and the grammar and syntax (relationship of words) of sentences. For those who do not read the original language, this becomes accessible by examining a variety of modern translations, or using an interlinear Bible (such as the free online Blue Letter Bible, . For example, Psalm 23:2 reads: “He makes me to lie down in green pastures.” I used to think that this described a verdant place with good-quality grass for the sheep to eat. But a closer look reveals that the Hebrew word used for “pasture” (na’vah) is not the normal word for a sheep’s feeding place; it means “comely, lovely, pleasant place.” The emphasis is upon beauty and pleasantness, not food. What is more, the Hebrew word for “green” (deshe’) is really a noun, not an adjective, referring to “tender, fresh soft grass” (cf. Prov. 27:25; The New Jerusalem Bible and the New English Translation Bible capture this picture). Habits of sheep verify this insight. Sheep do not eat lying down! The verse is not speaking of sheep eating (although this may be secondarily implied). The focus is on their place of comfort after their eating, as they are lying down, chewing their cud (ruminating) in a place of pleasant, fresh, soft grass. To apply this verse to us who are “the sheep of His pasture” (Ps. 100:3), God “causes us to lie down” sometimes, and invites us to “ruminate” over His Word.”5

IX. Theological Analysis

As one thinks of David writing about God as his shepherd, rich theological insights into the character of God emerge from the language he uses. For example, in Psalm 23:3 the shepherd leads the sheep “in the paths of righteousness for His name’s sake.” The phrase “for His name’s sake” indicates that the shepherd’s very name (reputation) is at stake as a good shepherd in making sure the sheep are safe. We see that God’s character is at stake in caring for His people, His sheep.

The psalm also holds a deeper meaning! Psalm 23 is sandwiched between two messianic psalms—Psalm 22, the Psalm of the Cross, and Psalm 24, the Psalm of the Crown (Christ’s ascension and entrance into heaven), making it likely that these three psalms form a “Messianic Trilogy.”6 The clues in Psalm 23 verify this conclusion.

Note, for example: the Shepherd’s Psalm was sung by a sheep (or lamb)!“The Lord is my shepherd.” On the deepest level, this sheep is none other than “the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29). He trusts His Father, the Shepherd. The messianic import of this psalm is supported by its literary structure highlighting key messianic terminology. As noted in the literary analysis section above, the climactic central verses of Psalm 23’s chiastic structure describe the two fundamental experiences of the Lamb: (1) “He leads me in the paths of righteousness” (verse 3) and (2) “though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death” (verse 4). Ultimately only the Lamb of God was both the Righteous One (Isa. 53:7, 11; cf. 1 Peter 1:19) and the one who passed through the shadow of death (as the sacrificial Paschal Lamb [1 Cor. 5:7]).

Psalm 22 is the Psalm of the Cross. Psalm 24 is the Psalm of the Crown. Psalm 23 is the Psalm of the Paschal Lamb!

X. Practical Contemporary Application

In light of the messianic interpretation of the psalm, we can “follow His steps” as God’s sheep (1 Peter 2:21, 25). The messianic dimension heightens its practical application to our lives. If Psalm 23 is ultimately about the Lamb of God trusting in His Shepherd, then it has even more precious relevance for us. We can walk in the steps of the Lamb of God (Jesus) and, like Him, trust in the Shepherd (the Father) as He leads us on the paths of righteousness and even through the valley of the shadow of death.

Conclusion

Applying the exegetical principles that emerge from Scripture allow us to plumb the depths of Scripture. In the Shepherd’s Psalm, following the clues of the contents and the contexts, we discover its Christ-centered focus (as with the rest of Scripture: Luke 24:27; John 5:39). The twenty-third psalm invites us to “exegete” the Lamb of God as He “exegeted” the Father (John 1:18), and then, walking in His steps, to “follow the Shepherd.” Exegesis is for everyone!

1 For further study, see Richard Davidson, “Interpreting Scripture: An Hermeneutical ‘Decalogue,’ ” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society 4, no. 2 (1993): 95-114. For more detail, see Richard Davidson, “Biblical Interpretation,” in Handbook of Seventh-day Adventist Theology, ed. Raoul Dederen, Commentary Reference Series (Hagerstown, Md.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 2000), vol. 12, pp. 58-104,. For application to Psalm 23, see Richard Davidson, “The Shepherd and the Exegetes: Hermeneutics Through the Lens of Psalm 23,” Current 4 (Fall 2016): 18-21,.

2 See Jerome L. Skinner, “The Historical Superscriptions of the Davidic Psalms: An Exegetical, Intertextual, and Methodological Analysis” (Ph.D. dissertation, Andrews University, 2016).

3 See, e.g., James K. Wallace, The Basque Sheepherder and the Shepherd Psalm (Vancouver: Graphos Press, 1956, 1970, 1977); W. Phillip Keller, A Shepherd Looks at Psalm 23 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1970, 1989).

4 For this basic structure, I am indebted to one of my students, Kevin Neidhardt, who wrote on this psalm for one of my seminary classes many years ago.

5 See Charles Allen, God’s Psychiatry: Healing Your Troubled Heart (Grand Rapids: Revell, 1984), for a powerful application of Psalm 23 to one’s spiritual experience.

6 For more details, see Richard Davidson, “Psalms 22, 23, and 24: A Messianic Trilogy?” in Reading the Psalms, vol. 2 of Songs of Struggle, Promise, and Hope (Berrien Springs, Mich.: ATS Publications, 2023), forthcoming.

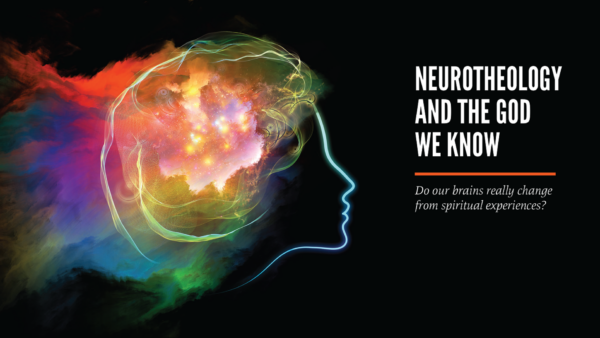

Is it possible to experience God by donning a helmet, like one would wear to play football or ride a bike? Are the experiences normally associated with activities such as prayer, fasting, or meditation artificially triggered by electrode–studded headgear authentically divine or just in our brains? Welcome to the brave new world of applied neurotheology.

When a few scientists decided to study religious phenomena, there was excitement in anticipation of what would be found, especially among people who live in both religious and science camps. “Will science finally demonstrate what adherents to religion have believed all along? Or would this be the death knell for religion and God?” These questions have been prevalent in the minds of both secular and religious thinkers alike.

In 1993 Drs. Eugene d’Aquili and Andrew Newberg from the University of Pennsylvania published a paper describing the then-modern interface between neuroscience and theology. Several names for this new discipline of neuroscience were tried: “spiritual neuroscience,” “biological theology,” and “neurotheology”—among others. The term “neurotheology,” first used in 1962 in the novel Island, stuck. What author Aldous Huxley meant by that term is debatable, but its current use conjures up a variety of fanciful notions that have led to speculations based on the “sound science” of neuroimaging and multidisciplinary neuroscience.

Anthropologists have observed that nearly all human societies have developed some form of religious or spiritual belief system, which may include the worship of gods or goddesses, the belief in an afterlife, or the practice of rituals. This universality has been documented in cultures as diverse as the ancient Egyptians and the contemporary Kung San people of the Kalahari Desert. Additionally, the idea of a supernatural being or higher power as well as the concept of an afterlife have been found in all known societies. Thus the interest in this widespread phenomenon of religion is born of true scientific curiosity.

Religious Experience Is Religious Experience

Neurotheological studies have shown specific neural correlates of religious or spiritual experiences, such as the activation of our default mode network (DMN) and the prefrontal cortex, and the participation of the brain chemicals serotonin and dopamine. Studies done with Buddhist monks meditating, Franciscan nuns praying, and Sikhs singing their prayers report all participants describing a feeling of oneness with the universe. Some neurotheologists conclude that “there is no Christian, no Jew, no Buddhist, no Muslim—it’s just all one.” And when it comes to the brain, religious experience is religious experience. They even echo the word of a certain Christian apostle who penned “There is neither Jew nor Greek . . . ; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28) in corroboration between Scripture and neuroscience. Nonbiblical forms of meditation and prayer are accompanied by changes in brain activity and connectivity in regions associated with self-referential processing, emotion, regulation, and attention, as well as reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety. Interestingly, the parietal lobes of the brain responsible for processing sensory information decrease activity during deep meditation, accompanied by a blurring of the boundaries between self and nonself and a sense of oneness with the universe.

Other observations should give us pause and ask further questions. It has been shown that taking a break from work, a short nap, going for a stroll, daydreaming, self-reflecting, or even mind-wandering can also activate the DMN. This network may appear to be very “spiritual” since it is involved in processing thoughts, emotions, and experiences, creating and imagining future scenarios and events, retrieving memories, understanding others’ perspectives and mental states, and processing moral and ethical decisions. So are all the activators of the DMN God-equivalents?

The author Carlos Castaneda, and the mystic occultist Aleister Crowley, long ago proposed the use of psychedelic drugs to induce mystical, transcendent states of consciousness before dopamine and serotonin were known. Alcohol and opioids do the same. So is God in the drugs? Researchers observe positive systemic changes in the brain and immune systems such as greater antibody response to virus exposure in just two months of meditation training. While this is considered a validation of meditation as a spiritual practice, there is evidence that listening to known and liked music—a nonspiritual practice—stimulates certain areas of the brain, and enhances the immune system. Is music, then, God?

A Different Brain

That scientists find the brains of people who spend significant amounts of time in prayer or meditation “different” from those who don’t should neither inspire awe nor welcome surprise since spending large amounts of anything (e.g., knitting, painting, reading)invariably leads to changes in the brain. The awe comes from the now-accepted fact that the brain can be rewired and retooled in the first place (i.e., it exhibits neuroplasticity). The brain can be sculpted much as muscles can from weight training. Mindful meditation is really deep focus. And when we focus on something—whether algebra, cricket, or food analysis—that thing becomes etched into the neural connections in our brains. By beholding we become changed, so we should be careful about what we focus on—sound advice found in Psalm 1 and Philippians 4:8.

The idea that our brains create the concept of God falls under the broader umbrella of neurotheology and is rejected as being radically unbiblical. Some neurotheologists argue that the human brain has evolved to seek out patterns and meaning in the world and that this tendency leads to the creation of religious beliefs and experiences to fill in the gaps in our understanding—the so-called God of the gaps. Some suggest that specific regions of the brain, such as the prefrontal cortex and the temporal lobes, may be responsible for religious experiences and the perception of a higher power. They go so far as to say that if God does not exist, our brains are wired to create Him. Still, others propose that religious experiences are the result of a complex interplay between biology, culture, and personal experience and that the concept of God is a product of human imagination rather than an objective reality.

All That Glitters

Neurotheology cannot be accepted lock, stock, and barrel. Some Christians may be enamored with the promising idea of proving the truth about God. But that is a promise that neurotheology cannot fulfill. First, it reduces religious experiences to mere brain activity. The scientific evidence is merely data that could lead to multiple interpretations. Phrenology was considered scientific when it was first introduced, and had a solid inferential, hypothetical framework. The measurement of cranial bumps was very precise in its day, much like images now produced by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans. The interpretation of the data was the problem, and ludicrous data-derived inferences led to ridiculous conclusions.

Further caution should be levied because of the possibility of manipulating religious experiences through brain stimulation and the characterization of people according to their ability to have mystical experiences. Is the idea of a “God helmet” ethical? Is the explanation for someone who wears such a helmet and doesn’t have the “experience” as being somehow genetically disadvantaged (and, by inference, spiritually disadvantaged) any less offensive than when the same arguments were used to disenfranchise people who didn’t have “certain patterns of bumps” on their skulls?

Neurotheology tends to overgeneralize its findings and often presupposes that the same neural mechanisms underlie all perceived religious or spiritual experiences. For Adventists, many of its described spiritual practices and experiences have little foundation in the canonical Scriptures. The emptying of one’s mind and the feelings of oneness with the universe were not described by Jesus or any of the prophets of the Bible as part of their religious lives. Much of neurotheology flies in the face of the teachings of Scripture, which starts with the words “In the beginning God . . .” The Bible never entertains the idea of “God maybe,” as some neuroscientists propose, but always “God is!” If the premises of neurotheology are true, then Jesus is a liar, and we create God, He didn’t create us. Some think that the future for bridging the gap between nonbiblical religions and atheistic science is bright because of neurotheology, but it is always wise to remember that in many things, all that glitters is not gold.

Passing around the corner from the dining room table, I heard one of my sons reading aloud from C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. I stopped and listened, knowing how much those Narnia books have meant to me. He was in the middle of a line, speaking fast and about to move on to the next paragraph. I stepped out into his view and said, “Stop there; read it again. It’s the most important sentence in the book.”